Third World Marxism: Revolution from the Periphery

Third World Marxism is a revolutionary ideology shaped by the experiences of colonized and oppressed peoples in the global South. Unlike classical Marxism, which focused on industrial Europe, Third World Marxism centers the struggles against imperialism, cultural erasure, and economic dependency. Its core pillars include anti-imperialism, cultural liberation, peasant-based revolution, total decolonization, economic self-reliance, and international solidarity. By adapting Marxist theory to local realities, Third World Marxists sought not only political independence but also social, cultural, and economic transformation, aiming to dismantle both colonial structures and mindsets. Their legacy continues to inspire movements for justice and liberation worldwide.

Musa Bey

9/15/20255 min read

Third World Marxism is more than a regional adaptation of a European ideology—it is a revolutionary framework forged in the crucible of colonialism, imperialism, and the global color line. It emerged not from the factories of Manchester or Berlin, but from the rice paddies of Vietnam, the sugar plantations of Cuba, the favelas of Brazil, and the mines of South Africa. While Marx and Engels focused their analysis on the contradictions of capitalism in industrial Europe, Third World Marxists re-centered that analysis to confront the contradictions of colonial domination, cultural erasure, and underdevelopment in the global South.

This essay explores the core pillars and beliefs of Third World Marxist ideology, situating them within their historical contexts and revolutionary praxis. These pillars—anti-imperialism, cultural liberation, peasant-based revolution, political decolonization, economic delinking, and internationalist solidarity—form the backbone of a tradition that reshaped Marxist thought from the margins of empire.

I. Pillar One: Anti-Imperialism as the Foremost Contradiction

At the heart of Third World Marxism is the belief that imperialism—not merely capitalism—is the fundamental contradiction of the modern world system. This distinction is crucial. While classical Marxism focused on class struggle within nations, Third World Marxism understood that capitalist exploitation operated internationally, and that the primary relationship of exploitation was between the Global North and the Global South.

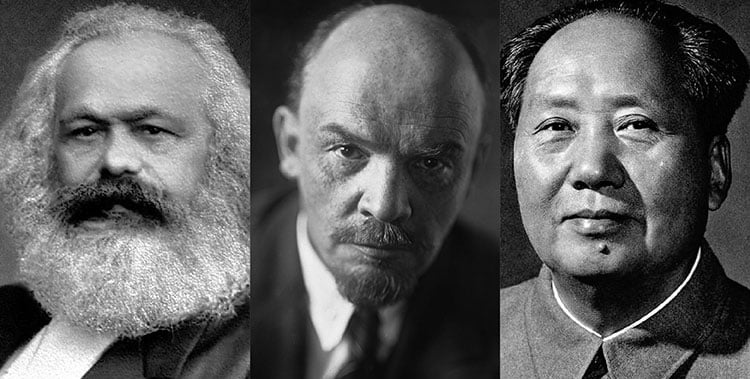

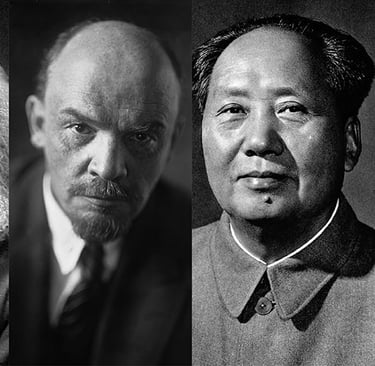

As Lenin theorized in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), the export of capital and the division of the world among colonial powers was no historical accident; it was the lifeblood of monopoly capitalism. But for Third World Marxists, Lenin only scratched the surface. Walter Rodney expanded on this in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, showing how colonialism was not simply about economic gain but about structurally sabotaging indigenous development.

For Third World revolutionaries, anti-imperialism was not a theoretical concern—it was a daily, lived reality. From Algeria’s war of independence to Vietnam’s struggle against U.S. imperialism, revolution was defined as the destruction of empire and the reclamation of sovereignty. Anti-imperialism became the guiding principle for movements from Palestine to Mozambique, from Nicaragua to Zimbabwe.

II. Pillar Two: Cultural Resistance and the Recovery of Identity

Unlike the materialist focus of orthodox Marxism, Third World Marxism placed a significant emphasis on culture as a battleground. Frantz Fanon and Amílcar Cabral both recognized that colonialism was not merely economic or political—it was psychological and cultural. It sought to erase the colonized’s sense of self-worth, history, and humanity.

Cabral famously argued that “culture is the seed of resistance.” For a people to liberate themselves, they had to rediscover and reclaim their cultural traditions, languages, and cosmologies. This was not a romantic nostalgia for the past but a recognition that colonial domination had severed people from their historical agency. Culture was both a weapon and a shield.

Fanon’s psychoanalytic approach showed how the colonized internalized inferiority and white supremacy. His call for cathartic violence was not only about seizing land or institutions—it was about reclaiming dignity. Third World Marxists saw cultural liberation as inseparable from material liberation. Songs, stories, names, hairstyles, dress, and language became sites of struggle.

III. Pillar Three: The Revolutionary Role of the Peasantry and Lumpenproletariat

European Marxism identified the industrial working class as the revolutionary agent of history. But in much of the Third World, the industrial proletariat was either small or non-existent. The vast majority of people were peasants, agricultural laborers, or what Fanon called the lumpenproletariat—those outside formal economic production.

This necessitated a radical revision of Marxist class theory. Mao Zedong’s Chinese revolution, grounded in peasant mobilization, provided an early model. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh followed a similar path. In Latin America, Che Guevara’s foco theory emphasized small guerrilla cells that could inspire and galvanize peasant uprisings.

Fanon was among the first to elevate the lumpenproletariat—not as “reactionary,” as Marx once claimed, but as revolutionary precisely because they had nothing to lose and everything to gain. In the slums, ghettos, and informal economies of the Third World, revolution would come not from organized unions but from the dispossessed, the unrecognized, and the abandoned.

This pillar emphasized the importance of mass participation, rural insurgency, and a flexible vanguard that could organize outside traditional class boundaries.

IV. Pillar Four: Decolonization as Total Revolution

Third World Marxists rejected the liberal notion that independence could be achieved through political reform or diplomatic negotiation alone. They understood decolonization as a total revolution—political, economic, psychological, and cultural.

Political independence without economic sovereignty, they argued, was a hollow victory. Former colonies often replaced white rulers with Black or brown elites who served foreign capital. This gave rise to the concept of neocolonialism, popularized by Kwame Nkrumah, where foreign domination persisted through debt, multinational corporations, puppet regimes, and international institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

For revolutionaries like Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso, true liberation meant overthrowing both colonial institutions and colonial mindsets. Land reform, women’s liberation, health care, and education were all part of the revolutionary project. Freedom was not just the absence of the colonizer—it was the presence of dignity, justice, and self-determination.

V. Pillar Five: Economic Delinking and Self-Reliance

In confronting global capitalism, Third World Marxists rejected the idea that development could be achieved by “catching up” to the West. Instead, they promoted economic delinking—a term coined by Samir Amin—which meant breaking the structural dependency on the capitalist core.

Dependency theory argued that the global South was poor because the North was rich. Raw materials flowed out; capital flowed in; value was extracted. The global economy was organized like a plantation, with the North as master and the South as servant.

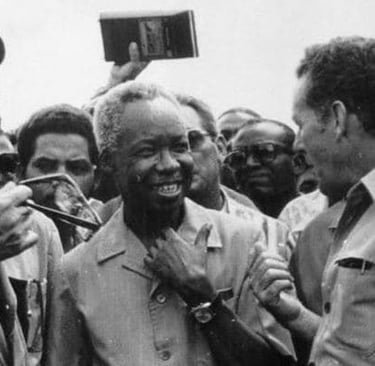

In response, Third World Marxists called for self-reliant development, nationalized industries, land redistribution, and state planning. Countries like Tanzania under Julius Nyerere, Mozambique under FRELIMO, and Nicaragua under the Sandinistas all experimented with socialist models aimed at serving the people, not the market.

This economic pillar challenged the myth of meritocracy, the idea of “rising through the system.” Instead, it insisted that the system itself must be dismantled.

VI. Pillar Six: Internationalism and Global Solidarity

Third World Marxism was inherently internationalist. Inspired by the Pan-Africanism of W.E.B. Du Bois, the tricontinentalism of Fidel Castro, and the solidarity of the Non-Aligned Movement, Third World Marxists viewed their struggles not as isolated nationalisms but as a united front against global imperialism.

The 1955 Bandung Conference was a watershed moment where Afro-Asian nations declared their right to exist independently of Western or Soviet domination. Later, Cuba became a hub of internationalist support, sending troops to Angola, medics to Africa, and weapons to liberation movements worldwide.

Third World Marxists believed that no nation could be free while others remained oppressed. Solidarity was not charity—it was shared resistance. They built transnational networks of revolution, creating a culture of global defiance against empire, racism, and capitalism.

This internationalism was not blind allegiance to the Soviet Union, either. Many Third World Marxists criticized Soviet authoritarianism and insisted on indigenous paths to socialism—autonomous, democratic, and rooted in local realities.

Conclusion: A Revolution Still Unfinished

Third World Marxism arose from the ashes of empire. It taught that liberation could not be outsourced, that revolution must be rooted in the specific soil of struggle, and that the oppressed are not passive victims but historical actors.

Though many of its governments were overthrown, betrayed, or crushed under neoliberalism and military coups, the vision of Third World Marxism endures. Its questions remain urgent: What does real independence look like? Can capitalism ever be just? What kind of world can we build from below?

In a time of climate collapse, mass displacement, and a rebranded colonialism called globalization, Third World Marxism remains not only relevant—but essential. It reminds us that revolution must start from the periphery, from the footnotes of history, and from the dreams of the wretched of the earth.